- The Malaysia Act would violate the Federation of Malaya agreement 1957 by abolishing the "Federation of Malaya".

- The proposed changes needed the consent of each of the constituent states including Kelantan, and this had not been obtained.

- The Sultan of Kelantan should have been made a party to the Malaysia Agreement.

- Constitutional convention dictated that consultation with rulers of individual states was required before substantial changes could be made to the constitution.

- The federal parliament had no power to legislate for Kelantan in matters that the state could legislate for on its own.

Saturday, 1 August 2015

Saturday, August 01, 2015

Agreement of Malaysia

,

Exposing the Truth

,

Fact

,

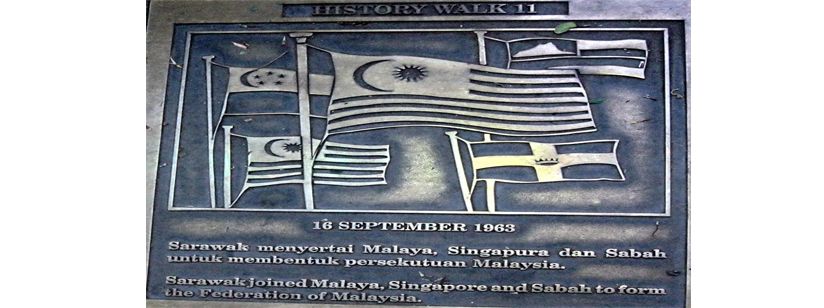

Federation of Malaysia 16 September 1963

No comments

Ramai Tak Tahu: Kelantan Pernah Cabar Penubuhan Malaysia Pada 1963 di Mahkamah

On July 9, 1963, the governments of the Federation of Malaya, the United Kingdom, Sarawak, North Borneo and Singapore signed the Malaysia Agreement that brought Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak into the federation.

The federal parliament then passed the Malaysia Act to amend the federal constitution to include the three new states and to provide for matters in connection with the admission.

On Sept 10 , six days before Malaysia was to be declared, the government of Kelantan began an action against the federal government for declarations that the Malaysia Agreement and the Malaysia Act were null and void or were not binding on the state.

In the case of The Government of the State of Kelantan v The Government of the Federation of Malaya and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj ("the Kelantan case"), Kelantan argued that:

Chief justice James Thomson delivered his decision 30 hours before Malaysia was to be declared, saying: "Never, I think, has a judge had to pronounce on an issue of such magnitude on so little notice and with so little time for consideration."

He added that "a clearer expression of opinion than would be customary is clearly required in a matter which relates to the interests of political stability in this part of Asia and the interests of 10 million people, about half a million of them being inhabitants of the state of Kelantan".

Thomson responded to the five different arguments forwarded by the Kelantan government by framing the issues into one general question of "whether parliament or the executive government has trespassed in any way the limits placed on their powers by the constitution".

In this way, he bypassed addressing some fundamental questions relating to the supremacy of the constitution raised by the Kelantan government. Nevertheless, he still managed to make several important constitutional pronouncements. The court said that even if Kelantan was a sovereign state prior to the 1957 Federation of Malaya Agreement, the effect of that agreement was that a large proportion of the powers that make up sovereignty passed from the Kelantan government to that of the federation.

These powers are thus limited to and subject to the 1957 Federal Constitution that formed part of the agreement. The court also found that the Malaysia Act in amending the constitution to admit the new states and changing the name to "Malaysia" did not contravene the requirements of the constitution, which were found to be liberal in such matters.

And if the steps that had been taken were in all respects lawful, the nature of the results they had produced could not make them unlawful.

What is now known as the "basic structure doctrine" stipulates that a constitutional amendment can be declared by the courts to be invalid on the grounds that it destroys the basic structure of the constitution.

The courts, therefore, must play a vital role in ensuring that the basic structure is not dismantled. It is within their function to interpret the constitution and determine what the basic features are.

With respect, the court in the Kelantan case missed the opportunity to make a pronouncement on this. There was certainly merit in the argument that theinclusion of the three new states with their different status and privileges as compared with the original 11 states created a fundamental change to the structure of the federation, at least in the eyes of Kelantan and the 10 other original members.

The Kelantan case, besides being a political challenge to the fundamental principle of equality found in the 1957 agreement, manifested into a legal pronouncement of the state of constitutionalism in the new federation.

It revealed that Kelantan and the other original states were placed together in a class of component states distinct and of a different status from the other three new states. This was the basis of the new federation.

The Kelantan government also, through this challenge, succeeded in opening a door upon a new sphere of constitutional interpretation. The chief justice gave approval to the possibility of there being implied limitations in the power of constitutional amendments.

Although subsequent judicial decisions in Malaysia did not show approval for this doctrine, they did not completely close the door that was opened by the Kelantan case. The future of constitutionalism and the supremacy of the constitution rest significantly on the continuous deliberation of the basic structure doctrine by our courts.

The Kelantan challenge was thus a significant chapter in Malaysian constitutional history. It resulted in establishing the constitutional relations between the component states of the federation, defining the path along which federalism in Malaysia will go.

In particular, this episode appears to have been a precursor of things to come for the constitutional and political relations between Kelantan and the federal government.