Wednesday, 29 July 2015

THE TWENTY POINTS AND THE DEVIATIONS IN IMPLEMENTATIONS

As already stated, the Twenty Points Memorandum came into being when five political parties representing the people of Sabah presented a united stand on the minimum safeguards considered by the Sabahan leaders as crucial, the acceptance of which would pave the way for the formation of the new Federation. This document is truly important because it embodies the needs and aspirations of the people of Sabah.

The views expressed in the Twenty Points were the basis of Sabah’s acceptance to be part of the Federation of Malaysia. Most of the Twenty Points were incorporated upon deliberation, into the Inter-Governmental Committee Report and the Malaysia Agreement.

It should be stressed here that while much energies and time were expended in deliberations on the constitutional safeguards, the mechanism for their implementation and protection from change, amendment or deviation was conveniently disregarded. Hence, with a powerful and all-embracing Malayan Government, insufficient attention was paid by the Sabah negotiating team as to how the assurances, undertaking and promises could be implemented once Sabah became a component of the Federation of Malaysia. Little attention was also paid to the subject of recourse which Sabah might take against the Federal government in the event of breach of the constitutional safeguards and assurances. The safeguards were negotiated in the spirit of a gentlemen’s agreement. It can be inferred that the absence of any provision in the 20 Points for a possible recourse which Sabah could take against the Federal government in the event of a breach of the constitutional safeguards and conditions was indicative more of the faith of Sabah’s leaders in former Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman and the Federal government’s assurances rather than the lack of foresight. To them a gentlemen’s agreement was sufficient guarantee, although later events have proven Sabah’s leaders wrong.

The Twenty Points are presented below together with a statement of their status in the context of the IGC, Malaysia Agreement and Federal Constitution. Comments pertaining to deviations in implementation, where appropriate, are outlined after the presentation of each point.

Point 1: Religion

While there was no objection to Islam being the national religion of Malaysia there should be no State religion in North Borneo, and the provision relating to Islam in the present Constitution of Malaya should not apply in North Borneo.

Comments:

In the IGC Report this point was taken up in the form of the provision that “Islam is the religion of the Federation” which essentially reaffirmed Article 3(1) of the Federal Constitution.

A contravention of this point occurred when the former Chief Minister of Sabah, Tun Mustapha enabled the passage of a constitutional amendment in the State Constitution thereby making Islam the State religion in 1973. It is well-known that Tun Mustapha actively discriminated against the promotion of other religions by expelling their missionaries. By this act, religious freedom which was intended by this point was abrogated in favour of Islam. His successor, Datuk Harris Salleh, also actively engaged in proselytization by using Islam as an instrument to grant favours to new converts. It was widely perceived by the general public that the actions of both Tun Mustapha and Datuk Harris were motivated by their need to strengthen their own political position vis-à-vis Kuala Lumpur.

In the case of the present Government, it tries to restore religious freedom by dealing with all religions equally but this is perceived as being anti-Islam. This is despite the fact that the State Legislative Assembly in 1986 inserted a new Article 5B “to confer on the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong the position of the Head of Islam in Sabah.”

Today, the status of Islam as the State religion has made it an instrument of political bigotry and provides a justification for religious polarisation and discrimination.

One may, of course, argue that the deviation that has occurred with respect to this particular point was caused by the State and not by the Federal authorities. This is too simplistic a view. As will be shown in Section V of the Memo, an examination of the Federal Government’s dealings with the State during the reign of the previous Chief Ministers shows numerous subtle interferences in Sabah’s political and administrative affairs by Kuala Lumpur, some of which are manifested in the form of administrative measures and decision making by Federal agencies. As a consequence, many constitutional amendments made at the State level which led to the dilution and surrender of several safeguards, were initiated and influenced by Federal Government. (e.g. Federalisation of Labuan).

Point 2: Language

(a) Malay should be the national language of the Federation;

(b) English should continue to be used for a period of time of ten years after Malaysia Day;

(c) English should be the official language of North Borneo, for all purposes, State or Federal, without limitation of time.

Comments:

Tun Mustapha’s administration changed the status of English by passing a bill, introducing a new clause 11A into the State Constitution, making Bahasa Malaysia the official language of the State Cabinet and State Legislative Assembly. At the same time, the National Language (Application) Enactment 1973 was passed purporting to approve the extension of an Act of parliament terminating or restricting the use of English language for other official purposes in Sabah. This is putting the cart before the horse, because the National Language Act 1963/67 was only amended in 1983 to allow it to be extended to Sabah by State Enactment. But, no such State Enactment has been passed. Therefore, the National Language Act 1963/67 is still not in force in Sabah. Nevertheless, the above amendments have brought about the following consequences:

(a) Many civil servants who were schooled in English are now employed as temporary or contract officers because of their inability to pass the Bahasa Malaysia examination.

(b) The change in the medium of instruction in schools affected the standard of teaching due to lack of qualified Bahasa Malaysia teachers.

(c) The teaching of other native languages has been relegated to the background.

Many Sabahans believe that the Constitutional Bill passed in 1973 to erode this safeguard was probably made on the advise and influence of syed Kechik, who was regarded as the KL’s man in Sabah. (See Ross-Larson(1980)).

Point 3: Constitution

Whilst accepting that the present Constitution of the Federation of Malaya should form the basis of the Constitution of Malaysia, the Constitution of Malaysia should be a completely new document drafted and agreed in the light of free association of States and should not be a series of amendments to a Constitution drafted and agreed by different States in totally different circumstances. A new Constitution for North Borneo was, of course, essential.

Comments:

It is obvious that the Sabah and Sarawak negotiating teams were of the opinion that they were joining in the Federation of Malaysia as equal partners, namely Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak. However, the request for a completely new Constitution was not granted thereby deviating from the basic agreement. The reasons offered were:

(a) Due to time constraint. The drafting of a completely new Constitution would take a long time to complete.

(b) The Sabah negotiating team recognised the amount of time and energy required to draft a new Constitution.

From the foregoing, it is clear that during the negotiation, the State leaders had shown complete trust and confidence in the capabilities of the Malayan leadership in honouring the assurances and promises given them. As a result, minimum fuss was made of the necessity of casting those promises and assurances in enforceable terms to be duly incorporated into official documents, complete with legal and constitutional recourse in the event of breaches. Furthermore, the readiness with which the State leaders consented to the use of Federal Constitution of Malaya as a basis on which new amendments were to be incorporated also illustrates the trusting nature of the State leaders then. However, the speed with which the formation of the Federation of Malaysia was hurriedly implemented, at a time when the people of Sabah were still constitutionally backward, leaves many present-day better educated Sabahans to question the extent of participation of the Sabahan leaders in the entire negotiation process. For such an important undertaking which affects the future of the people of Sabah, certainly more time should been given.

An important agreement reached by the Inter-Governmental Committee was that in certain aspects, the requirement of Sabah and Sarawak could appropriately be met by undertaking or assurances to be given by the government of the Federation of Malaya rather than by constitutional provision. Still, this was a clear deviation from what was requested in the Twenty Points.

Points 4: Head of the Federation

The Head of State in North Borneo should not be eligible for election as Head of the Federation.

Comments:

Since only a Ruler is eligible to be elected as the Head of the Federation in the Malayan Constitution, there was no necessity to make specific provision for the exclusion of the Head of the State of Sabah from election as Head of the Federation.

Point 5: Name of Federation

“Malaysia” but not “Melayu Raya”

Comments:

This point was incorporated into the IGC Report and subsequently into the Federal Constitution.

Point 6: Immigration

Control over immigration into any part of Malaysia from outside should rest with the Federal government but entry into North Borneo should also require the approval of the State government. The Federal government should not be able to veto the entry of persons into North Borneo for State government purposes except on strictly security grounds. North Borneo should have unfettered control over the movement of persons, other than those in Federal government employ, from other parts of Malaysia into North Borneo.

Comments:

While it was agreed in the IGC Report that the Immigration department should be a Federal department, the State should have absolute control of immigration to Sabah from within Malaysia.

Point 7: Right of Secession

There should be no right to secede from the Federation.

Comments:

There was absolutely no reason or need for this point to be listed since it is not a safeguard for the State but for the Federal government. Nevertheless, the amazing readiness of the five political parties to include this as one of the Twenty Points reflected their firm belief that the ‘marriage’ would be a permanent one. Their decision to concede the right to secession was no doubt motivated by the promise of improved economic well-being that the new Federation would bring and the respect with which the Federal government would place on agreed safeguards and assurances.

Point 8: Borneonisation

Borneonisation (Sabahanisation) of the public services should proceed as quickly as possible.

Comments:

As a consequence of Federal’s control on pensions (Article 112 of the Federal Constitution and Para 24 of the IGC Report), all promotions in the Federal department and creation of new posts in the State require Federal approval due to the “pension factor.”

An examination of existing records shows that the number of federalised departments or agencies in Sabah has increased 4 times since Independence. By 1985 there were 62 Federal departments and agencies in Sabah, of which more than 90 per cent is currently headed by Semenanjung officers. According to employment record, there are more than 21,000 Semenanjung officers working in government offices in Sabah. This is a clear deviation of the Twenty Points and IGC safeguards.

The usual justification used by the Federal Government to engage officers from Semenanjung to fill the federalised government positions is the lack of qualified Sabahans. However, it is found that even officers in the C and D categories are still being imported into the State from Kuala Lumpur. Furthermore, there has been no conscious plan to train prospective Sabahans to take over senior posts from these Semananjung officers.

At a time when some 800 graduates and thousands of school leavers in Sabah are unemployed, the existence of a large number of civil servants from Semenanjung serving in government departments gives many Sabahans the feeling that they have been deprived of employment opportunities which, in the context of the Twenty Points, are rightfully theirs.

Point 9: British Officers

Every effort should be made to encourage British Officers to remain in the public services until their places can be taken by suitably qualified people from North Borneo.

Comments:

This point was taken up and discussed extensively in the IGC Report.

Point 10: Citizenship

The recommendations in paragraph 148(k) of the Report of the Cobbold Commission should govern the citizenship rights of persons in the Federation of North Borneo subject to the following amendments:

(a) Subparagraph (I) should not contain the provision as to five years residence;

(b) In order to tie up with our law, subparagraph (II)(a) should read “seven out of ten years” instead of “eight out of twelve years”;

(c) Subparagraph (III) should not contain any restriction tied to the citizenship of parents – a person born in North Borneo after Malaysia must be a Federal Citizen.

Comments:

It is public knowledge that there is a significant number of Sabahans who were born before Malaysia Day is still having problems acquiring citizenship. Furthermore, many natives in the interior regions of the State are still holder of red I.C. because of the problems of verifying their birth.

It is also common knowledge that certain categories of refugees and illegal immigrants in Sabah have been issued with blue I.C. thus conferring upon them citizenship status and enabling them to vote in elections. This occurred particularly during the tenure of the previous State governments. A reliable source indicates that some 198,000 of these refugees have been issued with blue I.C.

According to a newspaper report, which was subsequently confirmed, police forces acting on public complaint raided Peting Bin Ali’s house in Sandakan on 16 November, 1979 and discovered that he was in possession of facilities to issue blue ICs. It is believed that the operators were collaborating with certain registration personnel in Kuala Lumpur. Most surprisingly the culprit was not prosecuted for committing such a grave crime against all the citizens of the country.

The process by which these illegals are registered by the Federal agencies for subsequent issuance of blue ICs, without due reference to the State, is considered by Sabahans as usurpation of the State’s immigration authority. This is a clear deviation from the safeguard on immigration and control of its franchise rights. Furthermore, the use of Labuan as an entry point to Sabah without immigration check, effectively removes immigration control from the State government.

Point 11: Tariff and Finance

North Borneo should have control of its own finance, development funds and tariffs.

Comments:

This illustrates the true feeling of the Sabah leaders concerning Malaysia. They saw Sabah as equal partner in Malaysia. With its vast natural resources not yet fully tapped and the promise of rich oil discoveries, the Sabah leaders foresaw that the State would have adequate financial resources to cater for its socio-economic development. Today, all proceeds of revenue other than those listed in Part III of the Ten Schedule are accrued to the Federal government. These include personal income tax, corporate tax, export and import duties, petroleum royalty, etc. The State government derives its incomes primarily from timber exploitation, copper mining, and since 1974, from the 5.0% petroleum royalty accorded to it.

A study conducted by Institute of Development Studies (Sabah) concludes that since 1976 there was a net transfer of financial resources out of Sabah in favour of the Federal government. It should also be borne in mind that much of the Federal government’s financial flow to Sabah has actually been in the form of operating expenditures to service the large numbers of federalised agencies in Sabah. Although, during the First and Second Malaysia Plan period the Federal government had spent more in Sabah than collected from it, however, since 1976 there has been a net outflow of funds from Sabah to the Federal government amounting to M$2,633.18 million in the Third Malaysia Plan period and M$4,871.46 million during the Fourth Malaysia Plan period. During the First, Second, Third and Fourth Malaysia Plan period, some 80.5%, 72.1%, 66.8% and 68.3% of the financial allocation to Sabah were for operating expenditures of Federal departments and agencies as shown below:

The substantial net outflow of funds from Sabah to Kuala Lumpur is perceived by Sabahans as siphoning off of Sabah’s development funds which is tantamount to financial exploitation of the State.

The understanding of the leaders in joining Malaysia was to achieve an accelerated pace of economic development. However, it appears that the bulk of the Federal funds currently spent in Sabah are for operating expenditures rather than for development purposes.

The overall level of financial allocation to Sabah by the Federal government can be considered as minimal relative to its socio-economic development needs. These allocations are indeed meagre when compared with the amount of financial resources derived by the Federal government from the State as shown by the table above.

It is further felt that the State’s share of its oil revenue (5%) is too small. The sequence of events which led Sabah to sign away its oil rights to the Federal government has continued to puzzle the minds of the Sabahans. Previous Chief Minister, Tun Mustapha and Tun Stephens had consistently refused to sign the Petroleum Sharing Agreement indicating their unwillingness to give up the State’s oil rights. It is interesting to note, however, that in the ensuing political crisis following immediately after the June 6, 1976 plane crash resulting in the death of most of the key BERJAYA leaders, Datuk Harris Salleh dramatically reversed the position of the State government by signing away the State’s oil rights.

To many Sabahans the signing away of Sabah’s oil rights is equivalent to Constitutional amendment. Many believe that unless approved by the State Assembly with a two-third majority, the Chief Minister’s signature alone does not constitute approval of the people of Sabah.

Point 12: Special Position of Indigenous Races

In principle, the indigenous races of North Borneo should enjoy special rights analogous to those enjoyed by Malay in Malaya, but the present Malaya formula in this regard is not necessarily applicable in North Borneo.

Comments:

While in principle the special privileges of Sabahan natives are recognised legally, the implementation of the policy has been somewhat dubious. For instance, when job vacancies in Semenanjung are advertised in national newspapers to the effect that “preference shall be given to bumiputera”, what it in effect implies is bumiputera of Malay origin and, inevitably the Malay in Semenanjung. This legacy was exported to Sabah during the reign of the government of Tun Mustapha and Datuk Harris. It is well-known that during those periods, the treatment accorded to indigenous people in the State depended on their religious faith. This gave rise to two categories of indigenous people – Muslim indigenous and non-Muslim indigenous. These actions always done in the name of ‘integration’ with the aim of presenting Kuala Lumpur the impression that the Muslim population in the State had grown rapidly. There were numerous cases during the reign of the previous governments where non-Muslim bumiputeras especially the Kadazans and Muruts, were bypassed for promotion or recruitment into the civil service unless they became Muslim.

Point 13: State Government

(a) The Chief Minister should be elected by unofficial members of Legislative Council;

(b) There should be a proper Ministerial system in North Borneo.

Comments:

The incorporation of this point in the IGC Report and Federal Constitution was consistent with the original intentions of the Sabah leaders.

Point 14: Transitional Period

This should be seven years and during such period legislative power must be left with the state of North Borneo by the Constitution and not merely delegated to the State government by the Federal government.

Comments:

This point was not addressed in the Malaysia Agreement nor dealt with in the Federal Constitution, even though the Cobbold Commission studied the point and recommended that the transitional period should be five years, or alternatively, minimum three years and maximum seven years. The ‘Transitional Period’ is actually discussed in Para 34 of the IGC Report and partly in Annex A to the Report.

It was clear that the purpose of introducing the transitional period was to provide the much needed time for the growth of political consciousness among the people of Sabah so that they would be able to understand their roles and responsibilities as political leaders. Both Malaya and Singapore had experienced a period of self-rule before Independence. Since neither Sabah nor Sarawak had any form of political relationship with Malaya and Singapore before the formation of Malaysia, a trial period would have significantly improved the Federal-State relationship right from the beginning. Had the transitional period been effected, it is generally believed that the erosion of constitutional safeguards may not have occurred so easily and rapidly.

Point 15: Education

The existing educational system of North Borneo should be maintained and for this reason it should be under State Control.

Comments:

The existing educational system referred to primary and secondary schools and teachers training colleges, but not university and post-graduate education. The Sabah delegation wanted to teach English at all levels of schools in the State as the medium of instruction. Malay and other vernacular languages, such as Kadazan and Chinese, were also to be taught and used as the media of instruction in lower level primary schools in some primary schools in some voluntary agency schools. It was the intention that the education policy and its development will be subject to constant adaption and would move towards a national concept but it should not merely be an extension of existing Federal policy.

In the IGC Report education was a federal subject although specific conditions were spelt out for its administration. The IGC Report also specified important conditions pertaining to education development in general including the use of English and implementation of indigenous education.

In 1965, the Sabah Education Ordinance No.9 of 1961 was declared a federal law. During Tun Mustapha’s reign, the State Constitution was amended to make way for the use of Malay as the sole official language by 1973. When the Peninsular introduced Malay as the medium of instruction in Primary One in 1970, Tun Mustapha’s Administration adopted the same policy in Sabah.

Since the Education Act, 1961, was extended to Sabah only in 1976, the introduction of the national Educational Policy to Sabah in late 60s and early 70s with the tacit consent of the then State government under Tun Mustapha was carried out without the proper legal authorities. However, this has been rectified by the extension of the Education Act, 1961.

It is also important to note that the IGC Report made specific references to the responsibilities of the Federal government in developing educational infrastructure in Malaysia, “the requirement of the Borneo States should be given special consideration and the desirability of locating some of the institutions in the Borneo States should be borne in mind.” By and large, the Federal government has done little for Sabah in the development of higher education facilities, aside from the setting up of a YS-ITM campus and a makeshift UKM branch campus. Even a donation by the State government of 364 hectares of land in 1980 to be developed into a permanent campus of the UKM together with a $5.0 million contribution from Yayasan Sabah failed to elicit the “special consideration” responsibility of the Federal government on the development of education infrastructure in Sabah as contained in the IGC Report.

Yet in Kedah, Universiti Utara Malaysia which was only established in 1984 enjoys the full financing and other support of the Federal government as compared to the Sabah branch of UKM which was established in 1974, or then years earlier.

Such a phenomenon does not only violate the “special consideration” clause supposedly accorded to Sabah but it also speaks of the inequity in the distribution of funds for educational purposes among components parts of the Federation of Malaysia.

Point 16: Constitutional Safeguard

No amendment, modification or withdrawal of any special safeguard granted to North Borneo should be made by the Central government without the positive concurrence of the government of the State of North Borneo. The power of amending the Constitution of the State of North Borneo should belong exclusively to the people in the State.

Comments:

Most of the safeguards contained in the IGC Report were incorporated into the Malaysia Agreement and subsequently into the Federal Constitution, although a number of these have since been repealed. In addition to the provision in the Constitution, Article VIII of the Malaysia Agreement provides that the governments of the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak will take such legislative, executive or other action as may be required to implement the assurances, undertakings and recommendations contained in Chapter 3 of, and Annexes A and B to, the Report of the IGC signed on 27th February, 1963, in so far as they are not implemented by expressed provision of the Constitution of Malaysia.

An additional important agreement reached by the IGC was that certain aspects of the requirements of Sabah could appropriately be met by undertakings or assurances to be given by the government of the Federation of Malaya rather than by Constitutional provision. The Committee further agreed that these undertakings and assurances could be included in formal agreement or could be dealt with in exchanges of letters between the governments concerned.

In the minds of the people of Sabah (and Sarawak), the inclusion of the safeguards in the Constitution was reassuring in that they were as good as guaranteed by the British government. There is, however, an oversight by those responsible for drafting the Constitution to ensure that these safeguards are to be really effective. An amendment to the Federal Constitution must be passed by a two-third majority by the Parliament (which in today’s composition of Parliament is a non-issue) and, where State rights are involved, it must have the consent of the State government concerned (i.e. the Executive). It does not have to be approved by the State Assembly (the representatives of the people of the State) by also a two-third majority. Under the present Constitutional arrangements, the safeguards are therefore as good only as the strength or personality of the State government of the day.

In essence, most of the safeguards can be abrogated by the mere ‘consent’ of the State government of the day, even for the sake of wanting to ‘please’ the Federal government. There is a general belief that this had been the case for previous governments in Sabah.

Para 30 of the IGC Report and Article 161E of the Federal Constitution provide the constitutional safeguards on some specific matters. While, Article 161E is not exhaustive, these are safeguards found in other constitutional provisions. Amendment to Article 3(3) (making the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong the Head of Islamic religion in Sabah) and repealed og Article 161A(1)(2)&(3) (relating to the special position of the Natives of Sabah) and Article 161D (relating to freedom of religion in the State) if made without the concurrence of the Yang Di-Pertuan Negeri contravenes Article 161E.

It should be pointed out that there are also cases where the Federal government failed to seek the concurrence of the State government in making amendments relating to matters under State control.

As regards Fisheries Act, 1985, marine and estuarine fishing and fisheries are in the Concurrent List whereas riverine and inland fishing and fisheries and turtles are in the State List. Therefore, both the State and Federal Legislatures can pass law on the former but only the State Legislature can pass law on the latter (except for the purpose of uniformity; but in such cases the law only come into force in the State if adopted by the State Legislature). In the event of conflict between State and Federal laws, the Federal Law will prevail. However, Sabah has its own Fishing Ordinance, 1963, but this was repealed by PUA 274/72 under section 74 of the Malaysia Act, 1963 apparently without the consent of the Head of State (Yang Di-Pertuan Negeri)

Similarly, when the Federal government put fishery matters as a supplement to the Concurrent List taken away from the State in 1976, concurrence was not sought from the State government. And when the Federal government repealed the Fishery Ordinance in 1978, again the State government was ignored. The Fisheries Department in Sabah is now in danger of being sued by the public because it is enforcing law upon which it has no power to it.

Point 17: Representation in Federal Parliament

This should take account not only of the population of North Borneo but also of its size and potentialities and in any case should not be less than that of Singapore.

Comments:

This point was taken up in the IGC Report and Malaysia Agreement. However, it is important to stress the fact that when considering representation in the Federal Parliament, the potentialities of Sabah should be taken into account and that the mention of the size of Singapore’s representation was only the minimum requirement. There are now 20 members from Sabah in the lower house of the Parliament. This particular point therefore remains ‘unbroken’. But since the signatories of the Malaysia Agreement consisted of the four governments of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah, there is a strong case for arguing that the matter should have been reviewed when Singapore pulled out from the Federation of Malaysia.

Indeed in view of Singapore’s departure from the Federation this safeguards must be reviewed along with other assurances in order to give the Malaysia Agreement validity. This review should be made immediately if Malaysia, as a federation, is to continue to be valid.

Point 18: Name of Head of State

Yang DiPertua Negara

Comments:

The name of the Head of State is Yang DiPertuan Negeri, as opposed to Yang DiPertua Negara as contained in both the Twenty Points and IGC Report. The use of the word ‘Negara’ by the Sabah leaders seems to convey the point that in their minds, independence was to bring with it a certain level of political autonomy for Sabah. It may therefore be argued that Sabah upon joining the Federation was a ‘negara’ or a nation. This clause was amended in 1976 in the Federal Constitution. Hence, the fact that this provision is not followed is a clear deviation.

Point 19: Name of State

Sabah

Comments:

This point was taken up in both the IGC Report and Malaysia Agreement.

Point 20: Land, Forest, Local Government etc.

The provision in the Constitution of the Federation in respect of the power of the National Land Council should not apply in North Borneo. Likewise the National Council for Local Government should not apply in North Borneo.

Comments:

While the State continue to exercise control over land, agriculture and forestry, the Federal government has established a National Land Council whose intention is yet to be determined. Should the National Land Council extend its jurisdiction over Sabah then it will contravene this particular provision.

In conclusion, it is shown that there are a number of critical areas in which the Federal government has deviated from the original spirit and meaning of the constitutional safeguards and assurances granted to Sabah at the formation of Malaysia. The basic conditions were contained in the memorandum called the “Twenty Points”, the contents of which were subsequently incorporated into the IGC Report, the Malaysia Agreement and Federal Constitution. The principle areas in which there have been clear deviations with respect to implementation are those which relate to matters pertaining to Immigration, Religious freedom, Borneonisation, Citizenship, Education, Finance, and Tariff Arrangements and Constitutional safeguards.

Deviations in implementation with respect to these matters have been largely responsible for strained Federal-State relations, thereby presenting barriers for territorial integration. It must nevertheless be stressed that problems pertaining to Federal-State relations do not originate merely from deviations as described above. Equally important is the problem of political interference by Kuala Lumpur in State affairs.

As a result of the deviations and political interferences, an idea is now slowly taking root that there is going to be a ‘take-over’ of the Borneo Territories by Malaya and the submersion of the individualities of Sabah and Sarawak.

Terkeluarlah Johor Daripada Malaysia

"Johor pun mula buka cerita lama. Kenapa kita di Sabah masih takut dan ragu-ragu? Kita berada 1600KM jauhnya dari Tanah Melayu berbanding Johor dan dipisahkan pula oleh Laut China Selatan. Kita ada budaya sendiri. Kita ada hasil bumi sendiri. Kita bukan hidup di tanah gersang. Kita mampu berdikari.

Tetapi kita memilih hidup bagai tanah jajahan. Kita memilih untuk meminta ehsan dalam setiap perkara. Membina jalanraya. Membina sekolah. Membina rumah ibadat. Membina kekuatan pertahanan. Menguruskan hasil bumi. Hampir semuanya harus menunggu kelulusan dari seberang. Sampai bila kita hidup bergantung sehingga kita tidak mampu menentukan halatuju kita? Apakah yang hendak kita wariskan kepada generasi akan datang?"

Nim Yorza

Subject of referendum very much alive among Sarawakians

OUTSPOKEN: When Home Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamid, in a statement published on March 13, said he would table an amendment to the Sedition Act to criminalise secession calls by Sarawak and Sabah, an ad hoc group of five Sarawakians and Sabahans went on a hunger strike at Dataran Merdeka in Kuala Lumpur.

After four days, they ended their hunger strike when they came to learn that the amendment was unlikely to be tabled.

Pujut assemblyman Fong Pau Teck who led the group was later quoted as saying, “The proposed amendment is outdated colonial law, which is ultra vires the Federal Constitution and in breach of international law principles.

“It is the right of Sarawak to be consulted on any issue affecting the position of Sarawak in the Federation of Malaysia. This is the basic safeguard upon the founding of Malaysia that any federal legislation which affects the rights and status of Sarawak in Malaysia must first be agreed to by the people of Sarawak.”

Elsewhere in the country, Lina Soo, former president of Sarawak Association for People's Association (Sapa), declared an unlawful society by the Home Ministry before the Umno general assembly in November last year, said: “According to legal opinions that we have gathered, the people of Sarawak and Sabah can challenge the amendments because it is ultra vires the Malaysia Agreement and Constitution.

“We members of the Concerned Sarawakians Group are sending out letters to all Sarawakian members of Parliament and state assembly members for them to take action against the amendments.”

Constitutional law expert Robert Pei, in an interview with the Malay Mail, quoted a statement by the Inter-Governmental Committee (IGC) Report chairman Lord Lansdowne when answering questions during the debate on the Malaysian Agreement in the Sarawak State Legislative Council that “any State voluntarily entering a federation had an intrinsic right to secede at will, and that it was therefore unnecessary to include it in the Constitution.”

“So it appears that the right to secede still exists otherwise Umno would not have bothered to want to ban this right,” Pei said, adding that it is a requirement of the Malaysia Agreement and Constitution that any amendments affecting the Malaysia formation rights of Sarawak and Sabah cannot be done without prior consultation and agreement of the two states and a two-thirds majority in Parliament to amend the Constitution.

The Malay Mail reported:

“He (Pei) said it would further be illegal for the Sarawak and Sabah governments to agree with such an amendment as neither they nor the Malaysian Government and Opposition have any mandate to make this amendment.

“Failure to comply with this legal requirement, he said, would certainly be a breach of the Malaysia Agreement 1963 and clearly ultra vires the Constitution.

“Pei concluded that since the amendment is intended to directly abrogate a fundamental right of the Sarawak and Sabah peoples, a referendum should be held to allow the people to decide on the issue.”

The subject of a referendum has not died down.

On July 12, it once again emerged, this time from Sarawak United People’s Party (SUPP) deputy secretary-general Sih Hua Tong.

In a Borneo Post report, Sih has urged Parliament to look into the feasibility of tabling and passing a Referendum Bill “to provide a means for Malaysians to address and solve major issues that are too critical for MPs alone to decide”.

“Why are Sarawakians and Sabahans not allowed to review the legal documents, their rights and so on?” he argued as he referred to the Sedition Act 1948, which looks unkindly at Malaysians touching on the independence of the two Borneo states.

Describing the restriction as unfair, Sih said Sarawakians have been deprived of their basic rights despite the non-existence of any legal or standing documents saying that they cannot review their rights.

“This is definitely against the will of Sarawakians and Sabahans,” Sih was quoted as saying.

The Borneo Post wrote: “Asked whether he was for or against the independence of Sarawak, Sih said: ‘I reserve my stand. The majority of Sarawakians should have a say over the fate of Sarawak while the views of a few individuals are not important.’”

Where does the right of Sarawakians to decide their fate lie?

Dr Ooi Keat Gin, a lecturer in Universiti Sains Malaysia’s School of Humanities and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society of Britain, says it is in the numerous safeguards incorporated into the constitutional arrangements made when Sarawak, together with Sabah (then called North Borneo) and Singapore, joined the wider federation of Malaysia in 1963.

These safeguards are what constitute the Malaysia Agreement 1963.

Ooi wrote: “On July 9, 1963, Temenggong Jugah anak Barieng, Datu Bandar Abang Haji Mustapha, and Ling Beng Siew, as Sarawak’s representatives, penned their signature to the Malaysia Agreement in London.

“Did they realise what they were signing and did they really represent Sarawak? Jugah in particular did not know how to read or write (according to a fairly authentic rumour he could sign his name by following a tattoo of it on the inside of his left forearm), Abang Mustapha was a representative of the Kuching Malays – seen by many Sarawakians as collaborators with the British colonial regime and Ling Beng Siew of the rich Sibu Foochow Chinese – who had nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

Over the years these safeguards have been dismembered and dissected and the Malaysia Agreement downtrodden and disrespected.

Apparently Malayans were only interested in hegemonic control and interference over the states of Sarawak and Sabah. Theirs was a scheme cooked up to replace British hegemony with Malayan hegemony.

According to Ooi, the signatories to the Malaysia Agreement did not realise – the truth was hidden from them – that Malaya had then reached the limit of its economic resources and required a new pool of resources upon which to further develop itself, and which was to be provided by Sarawak and Sabah at their own expense and to their own detriment.

“One of the main safeguards which they forgot was to keep their petroleum resources for themselves. The Malayans were glad to be silent on this, since they knew that under international law, offshore petroleum resources belonged to the federal government,” Ooi wrote.

But if the signatories to the Malaysia Agreement failed to read the situation, SUPP was Sarawak’s most vocal voice of anti-federation of Malaysia.

According to Ooi, SUPP’s uncompromising stance received initial support from Sarawak National Party (SNAP) led by Stephen Kalong Ningkan who maintained that, “Any attempt to put Sarawak under the influence and subjection of any foreign power would be strongly opposed.”

“That foreign power was and still is Malaya,” said Ooi.

What could be learnt from this piece of history is that SUPP asking for a Referendum Bill today shows the party has not strayed far from the path taken by the SUPP of pre-independence days.

In fact, if one cares to delve a bit deeper into the days leading up to the formation of Malaysia, the majority of Sarawakians did not understand the Malaysia proposal.

A so-called referendum conducted by Lord Cobbold was at best a hoax. Ignorant, illiterate Dayaks asked to make a stand merely said, “Barang ko’ nuan, Tuan” (Whatever you say, Sir).

In the words of the late Tra Zahnder, a member of the Council Negri then, most of the native population, “appear to know nothing or little about (the) Malaysia (proposal) but agree to it because they have been told that Malaysia is good for them”.

Fifty years today, Sarawakians think a serious mistake had been committed; a referendum looks to be the perfect solution.

Chronology of Sarawak throughout the Brooke Era to Malaysia Day

1835 Beginning of the Sarawak Rebellion (against the Sultan of Brunei) led by Sarawak chief Datu Patinggi Ali.

1839 James Brooke arrives in Kuching on the Royalist carrying a message of thanks and presents from the Governor of Singapore to Rajah Muda Hassim in Sarawak.

He returns later and at the request of the Rajah Muda Hassim, the Sultan of Brunei, suppresses the rebellion.

Sept 21 1841 Brooke made rajah and governor of Sarawak after Rajah Muda Hassim dismisses Makota.

1845 The battle of Marudu Bay sees Brooke enlisting the help of the British Royal Navy in Singapore to defeat Sherif Osman, a famous pirate leader from North Borneo, effectively ending his piracy.

1846 Sultan of Brunei unhappy with the English and Brooke.

His fi rst move against Brooke is to order the killing of Englishmen and everybody in Brunei close to him, which includes Rajah Muda Hassim, his brother Badruddin and other leaders in Brunei.

Brooke attacks Brunei in retaliation. Assisted by the British navy, they capture the city.

The Sultan is allowed to return to his palace after surrendering.

In addition he gives Sarawak completely to Brooke and his heirs forever without payment of any more money.

In memory of Rajah Muda Hassim and Badruddin, he gives two streets in Kuching their names: Jalan Muda Hassim and Badruddin Road. Later, two of his nephews, James and Charles Johnson come to Sarawak to help him.

James is given the title Tuan Besar and later, Rajah Muda.

Charles Johnson is called the Tuan Muda and changes his name to Charles Brooke later when he becomes the second rajah of Sarawak.

1849 The Battle of Beting Maru sees Brooke defeating Iban pirate chief named Linggir.

He is helped by Captain Farquhar, his ships of the Royal Navy and by Malay and Dayak in prahus.

Altogether there are about 75 boats and 3,500 men on Brooke’s side.

After a hard fight for several hours in the darkness, many pirate ships are sunk and hundreds of pirates killed or captured.

Brooke builds forts at Lingga and the mouth of the Skrang River on Batang Lupar to prevent more attacks.

1850 The US recognises Sarawak.

1852 Sarawak’s territory expands.

1853 Sarawak extended to the Krian River.

1855 Brooke starts the Supreme Council made up of a small group of important officers in Sarawak to help him govern the country.

1857 Kuching sacked by Chinese rebels.

Six hundred Chinese miners from Bau sail down the Sarawak river at night to attack the Astana, the government buildings and the fort. Much of Kuching is razed to the ground except for the Chinese areas.

Brooke retaliates by enlisting the help of loyal Malays.

Charles sails quickly from Lingga with Iban soldiers.

The rebels retreat up river and are chased to Bau and to the Dutch Borneo border where they try to escape to Sambas and Pontianak.

As many as 1,000 Chinese rebels and their families are killed.

1861 After their defeat at sea, pirates move farther inland to continue attacking villages and capturing heads.

The chief leader is an Iban named Libau, better known as Rentap.

From his Bukit Sadok fort, he leads his men to attack villages or the Rajah’s forts along the Batang Lupar.

After two unsuccessful counter-attacks, Charles becomes more determined to capture Rentap’s fort at Bukit Sadok.

He builds a twelve-pounder cannon in Kuching which takes 500 of his men to pull through the jungle to Bukit Sadok. Once there, 60 of his strongest men lift the cannon on poles and carry it to the top of Bukit Sadok 3,000 feet high.

The cannon fi re penetrates Rentap’s sturdy fort made of thick belian wood.

They discover, however, that the pirate leader has run off into the jungle and burn his fort.

Rentap is never to be heard of again.

1861 Sarawak is extended to Kidurong Point.

An offer by King Leopold I. of Belgium to purchase Sarawak is not successful.

1862 The Sarawak regiment.

Is created.

1863 Sarawak Dollar introduced.

1864 Britain recognises Sarawak as an independent principality.

1865 Charles forms the Council Negri which include people in the Supreme Council, other officers of the rajah’s government and the most important native chiefs.

1867 Council Negri holds its first meeting in Sibu.

1868 James Brooke is succeeded by his nephew Charles.

Brooke returns to England due to ill health and dies there.

1869 Sarawak begins issuing postage stamps.

1870 Sarawak Gazette begins publication.

1872 The name of the town of ‘Sarawak’ is changed to Kuching where it reportedly gets its name from a small brook which ran into the Sarawak River near the present Chinese Chamber of Commerce Building at the end of Main Bazaar.

1883 Sarawak extended to Baram River.

1884 Great fi re of Kuching. 1885 Acquisition of the Limbang area, from Brunei.

1888 Sarawak declared a British protectorate.

1890 Limbang added to Sarawak.

1891 Opening of the Sarawak Museum.

The border between Sarawak and Dutch Borneo is decided at a meeting between Great Britain and the Netherlands (Holland) whereupon it is decided that the border would follow as closely as possible the line of the highest mountains between Sarawak and Dutch Borneo.

1901 Sarawak’s population is 320,000 1903. Oil discovered in Sarawak.

1905 Acquisition of the Lawas Region, from Brunei.

Sarawak spans 47,000 square miles.

1912 Brooke Dry Dock opened. 1915 First railway line in Sarawak opened.

1915 Committee of Administration, seated in Kuching, established.

A 10-mile railway going south from Kuching fi rst used.

1917 Charles Vyner Brooke succeeds his father Charles as Rajah.

1924 Sarawak Penal Code introduced.

1925 Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China builds its first offi ce in Kuching to take care of the payment for Sarawak;s increasing business with other countries. 1931 Penghulu Asun leads a small rebellion among the Ibans against the government in the headwaters of the Kanowit, Entabai and Julau Rivers.

Vyner Brooke sends a police expedition up the Kanowit River and captures Asun and most of the other leaders.

Fort Brooke is built at Nanga Meluan on the Kanowit River.

Asun dies of old age in 1958. 1938 Kuching airport opened.

1941 Written constitution granted.

1941 Sarawak has a population of 490,000.

Dec 161941 Japanese occupy Miri.

Dec 19 1941 Japanese bomb Kuching.

Dec 24 1941 Japanese attack and capture Kuching.

1942-1945 Japanese occupation.

August 14 1945 Japanese surrender.

Sept 11 1945 Australian forces liberate Sarawak.

1945-1946 Sarawak is put under Australia’s military administration.

May 1946 Council Negri meets to talk about cession to British government.

They agree that Sarawak should become a colony by a vote of 19 to 16.

July 1 1946 Government passes a law that accepts Sarawak as a British Crown Colony.

1946 Sarawak becomes British crown colony.

1949 Governor Duncan Stewart is assassinated.

1957 Sarawak gets a new constitution which changes the size and powers of the Council Negri.

Council Negri is increased to 45 members.

1959 First general election held in Sarawak.

1961 May 27 Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister of Persekutuan Tanah Melayu, at a Foreign Correspondents’ Association of Southeast Asia press conference in Singapore, says the Federation of Malaya should have a close understanding with Britain and the people of Sarawak, Brunei and Sabah.

June 20 Sir Harold Macmillan, British Prime Minister, in a reply to a question in Parliament, says he is interested in the suggestion made by Tunku.

June 26 British offi cers from Singapore, Sarawak, Brunei and Sabah, consisting of governors, hold a meeting in Singapore until June 27.

July 1 Tunku Abdul Rahman accompanies the Yang Di- Pertuan Agong of Malaya to offi cially visit Brunei and Sarawak. July 9 Azahari (Partai Rakyat Brunei), Ong Kee Hui (Sarawak United People’s Party) and Donald Stephens (Sabah) establish the United Front and disagrees with the proposal by Tunku Abdul Rahman and Britain.

July 12 Tunku Abdul Rahman exposes communist threats in South East Asia as an important factor in his proposal.

July 22 Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore chief minister, proposes that representatives from Sarawak, Brunei and Sabah present their views at the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) on the Malaysia proposal.

July 28 Establishment of the Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee (MSCC) in Singapore during the CPA Conference.

August 12 First visit of leaders from Sarawak and Sabah – Datu Bandar Abang Mustapa, Temenggong Jugah, Donald Stephens and Dato Mustapha – to Malaya to see the progress for themselves.

Many such visits are organised for leaders in Sarawak and Sabah up till the formation of Malaysia.

August 24 MSCC holds its fi rst meeting in Jesselton (now Kota Kinabalu) in North Borneo (Sabah).

Brunei did not attend.

October 16 A motion for the formation of Malaysia is tabled in Parliament by Tunku Abdul Rahman and is approved.

November 23 Malaya negotiates with Britain to amend the Defence Agreement to expand British assistance when Malaysia is formed and to maintain their army camps.

Malaya and Britain negotiate and agree on the setting up of an investigative commission on the formation of Malaysia.

December Parti Barisan Anak Jati Sarawak (Barjasa) is registered.

Political parties formed earlier are the Sarawak United People’s Party (SUPP) on 12 June 1959, Parti Negara Sarawak (Panas) on 9 April 1960 and Sarawak National Party (SNAP) on 10 April 1961.

These older parties are formed for local council and district elections that started in 1959.

December 18 MSCC holds its second meeting in Kuching.

Brunei attends only as observer.

December 20 The stand of Sarawak and Sabah shifts from opposition to bargaining on issues such as representation in parliament, freedom of religion, national language, civil service, immigration and economic development as stated in a press statement at the end of the MSCC meeting.

December 30 During a conference in Jakarta, Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), the third largest communist party in the world, condemns the formation of Malaysia as a British neo-colonist ploy.

1962 January 4 British colonial government in Sarawak publishes a white paper on Sarawak’s consent for Malaysia and the establishment of an investigative commission proposed by the governments of Malaya and Britain on November 23, 1961.

The White Paper is translated into local dialects and widely distributed in Sarawak.

January 8 MSCC holds its third meeting on constitution and politics in Kuala Lumpur.

A decision is reached to produce all the proceedings for public consumption just as the British colonial government had done in Sarawak. January 31 British colonial government in Sabah produces a white paper, similar to the one published in Sarawak.

It is also translated into local languages and distributed widely.

February 1 MSCC holds its fourth and last meeting in Singapore.

February 3 All MSCC delegates sign a memorandum of proposals and recommendations which is then published in Sarawak and Sabah.

The Cobbold Commission is set up to seek the views of the people of Sarawak and Sabah on the formation of Malaysia.

Members of the commission are Lord Cobbold (chairman), Sir Anthony Abell and Sir David Watheraton (British representatives) Dato Wong Pow and Ghazali Shafie (representatives of Malaya).

February 19 The Cobbold Commission arrives in Kuching to begin public hearings at 35 centres.

March 6 Deputy Prime Minister of Malaya, Tun Abdul Razak, said that at that time only Britain and the Philippines were involved in the territorial claims over Sabah.

April 17 The Cobbold Commission completes its task in Sarawak and fl ies to Jesselton to continue its investigations at 15 centres in Sabah.

April 24 The legislative assembly of the Philippines unanimously approve “Resolution No.7… the President of the Republic to take the necessary steps consistent with international law and procedure for the recovery of a certain portion of the Island of Borneo and adjacent islands which appertain to the Philippines”.

April 29 Sultan of Sulu hands over the rule of Sulu (which has never been colonised by Spain or the United States of America) to the Philippines until she was accepted as an independent sovereign country.

May 24 The British government sends a memorandum to the ruler of the Philippines on its claim to a part of Sabah.

The other part was previously under the Brunei sultanate, particularly along the west coast.

June 22 The ruler of the Philippines sends a note to the British government on its claim over Sabah.

June 24 Donald Stephen, President United Kadazan Organisation (UNKO), says the people of Sabah challenge the claim by the Philippines.

June 27 Sarawak Chinese Association (SCA) Party formed.

July The Cobbold Commission sends its report to the government of Malaya and Britain .

July 18 Sultan Omar Ali Saifudin, Sultan Brunei, declares that Brunei will join Malaysia separately from Sarawak and Sabah.

July 20 Parti Pesaka formed.

The ruler of the Philippines sends a note on its Sabah claim to the government of Malaya.

August 1 Negotiations on the Cobbold Report between Malaya led by Tunku Abdul Rahman and his colleague from Britain to announce the formation of the Federation of Malaysia on August 31, 1963 after it is approved by their respective legislatures.

August 30 Inter – Government Committee (IGC) holds a preparatory meeting in Jesselton, Sabah, and sets up its headquarters there.

Sabah political parties submit the Twenty Points claim to Deputy Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya Tun Abdul Razak and Lord Landsowne in Jesselton.

September 12 The Sabah State Legislative Assembly unanimously approves the formation of the Federation of Malaysia and the establishment of the IGC.

September 26 The Sarawak State Legislative Assembly unanimously approves the formation of the Federation of Malaysia and the establishment of the IGC.

The Sabah Alliance is set up by Pasok Momogun, Sabah United Party, United Kadazan Organization (UNKO) and United Sabah National Organization (USNO).

September Philippines Vice President, Emmanuel Paleaez, declares his country’s claims to a part of Sabah at the United Nations, New York. October 16 Sabah Alliance declares the opposition of the people of Sabah on the claim of the Philippines.

December Sabah Alliance wins the election with 131 out of 137 contested constituencies with a manifesto based on the Twenty Points.

December 8 Partai Rakyat Brunei causes a revolt in Brunei, Limbang, Lawas and Miri.

December 9 A M Azahari, Partai Rakyat Brunei chairman, announces the North Kalimantan Revolution Government while in exile in Manila. He is actually a citizen of Lebanon; his father had married the daughter of Hugh Low, the British Governor of Labuan, who had married a Sarawakian woman, Dayang Loyang.

December 20 IGC holds its last meeting in Kuala Lumpur.

It had held 24 meetings in Kuching, Jeselton, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur.

1963 January 5 Curfew from 6pm to 6am is enforced in Limbang. January 8 The Governor declares as illegal the Sarawak Farmers’ Association, Kesatuan Rakyat Insaf Sarawak, Chung Hua Alumni Association Sibu, Tentera Nasional Kalimantan Utara, Angkatan Dosu Berantu and Angkatan Rakyat Anak Sabah.

January 28 British Foreign Secretary Lord Home and Philippines Vice President Emmanuel Palaez begins negotiations on claims over Sabah until February 1 with no results.

Diosado Macapagal, the President of the Philippines states for the fi rst time his country’s opposition to the formation of Malaysia in his state-of-thenation speech in the Philippines Congress.

February 11 Dr Subandario, Indonesia Foreign Minister, officially objects to the formation of Malaysia.

February 23 IGC submits Reports to the Governments of the Four Parties Concerned – Britain, Malaya, Sarawak and Sabah.

The IGC report is published. March 8 Sarawak State Legislative Assembly unanimously adopts the recommendations in the IGC report.

March 13 Sabah State Legislative Assembly adopts recommendations in the IGC report.

April Sarawak local council elections are held until June.

May 15 Third Rajah Sir Charles Vyner Brooke passes away in England.

May 31 Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister of Malaya and Sukarno, President of the Republic of Indonesia negotiate in Tokyo for an agreement o n the formation of Malaysia and to stop Indonesia from sending her army into Sarawak and Sabah.

June18 The Sarawak Flag will use the old fl ag with a crown in the centre.

June19 The results of the election are announced – Alliance 78, Independent 67, SUPP 16 and Panas 11. June 20 31 Independent legislators join Alliance, bringing the tally to 119.

July 9 The Malaysia Agreement is reached by Britain, Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah.

Brunei withdraws at the last moment.

It is signed by Temenggong Jugah, Dato Bandar Abang Mustapa, Abang Openg, Ling Beng Siew and PEH Pike.

From Sabah are Donald Stephens, Dato Mustapha, Khoo Siak Chiew, G S Sundang, WS Holley, and WKH Jones.

From Singapore are Lee Kuan Yew, and the representatives of Malaya and Britain are Tunku Abdul Rahman and Harold Macmillan respectively.

July 19 British House of Commons approves the Malaysia Bill to enable Sarawak and Sabah to form Malaysia.

July 22 Stephen Kalong Ningkan chosen as the first Chief Minister of Sarawak along with the state’s first cabinet.

July 30 Tunku Abdul Rahman, Sukarno and Macapagal meet at the Manila Summit.

August 5 Manila Summit ends resulting in Manila Declaration in which the three countries agree to form a new confederation called Maphilindo (short for Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia).

There is also a Manila Accord in which the three countries agree to work together in politics, economics, socially and culturally.

Philippines and Indonesia request that the Secretary General of the United Nations get the views of the people of Sarawak and Sabah on the formation of Malaysia.

August 3 Governor Sir Alexander Waddel launches the 1962 uprising memorial for British commandos who were defeated in Limbang.

August 6 Teo Kui Seng, Natural Resources Minister, also the chairman of the Malaysia Day celebration, announces the programme.

August 8 Sabah Legislative Assembly unanimously passes the Merdeka motion to join Malaysia and also approves the Malaysia Agreement.

August 15 Parliament of the Federation of Malaysia approves the Malaysia Agreement.

August 16 United Nation Malaysia Mission (UNMM) arrives and carries out its task to get the opinion of the people of Sarawak and Sabah until September 5, 1963.

Their arrival is also met with anti-Malaysia protestors at the Kuching Airport.

August18 Indonesian soldiers and insurgents invade Sungai Bangkit in Song, resulting in a casualty.

August 19 Abdul Taib Mahmud, Communication and Works Minister, visits the headquarters of the Public Works Department in Kuching.

The merdeka celebration is postponed from August 31 to September 16.

August 26 Yang Di-Pertuan Agong of Malaya approves the Malaysian constitution. August 27 Demonstrations against Malaysia in Sibu in connection with the arrival of the UNMM team.

August 29 Yang Di-Pertuan Agong signs the Malaysia Declaration, fi xed on September 16, 1963.

Anti-Malaysia protest in Miri on the arrival of the UNMM team results in a clash with the police. August 30 UNMM team arrives in Limbang, its last stop.

September 1 UNMM representative, Lawrence Michelmore, meets representatives from Alliance and SUPP at the State Legislative Assembly chambers.

September 4 Sarawak Legislative Assembly approves Malaysia motion with 38 votes for and fi ve against.

Stephen Kalong Ningkan tables the motion which states: “Be it resolved that this Council reaffirms its support for Malaysia, endorses the formal agreement which was signed in London on the 9th July and, while regretting that the Federation of Malaysia could not be brought into being on the 31st August, welcomes the decision to establish it on the 16th September, 1963.” September 5 UNMM team leaves Sarawak.

September 11 Chief Minister, Stephen Kalong Ningkan, and three ministers as well as 10 members of the Alliance fl y to Kuala Lumpur to meet the Prime Minister and the Secretary of the Colony of Britain, Duncan Sandys. September 13 UNMM presents its report.

“The Mission is satisfi ed that through its hearings it was able to reach a crosssection of the population in all walks of life and that the expressions of opinion that it heard represent the views of a sizeable majority of the population.

The Mission is convinced that the time devoted to hearings and the number of localities visited was adequate and enabled it to fully carry out its terms of references.”

Sir Alexander Waddell announces that Datu Abang Openg is appointed by the Yang Di-Pertuan as the first Yang Di-Pertua of Sarawak beginning from Malaysia Day.

Temenggong Jugah Barieng is appointed to the Federal Cabinet as the Sarawak Affairs Minister.

September 14 Duncan Sandys arrives in Kuching for a brief visit. September 15 Dr M Sockalingam is appointed as the Speaker of the Sarawak Dewan Undangan Negeri.

British colonial Governor, Sir Alexander Waddell, and wife leave Astana, the offi cial Brooke residence and that of British governors since 1870, at exactly 12.30pm.

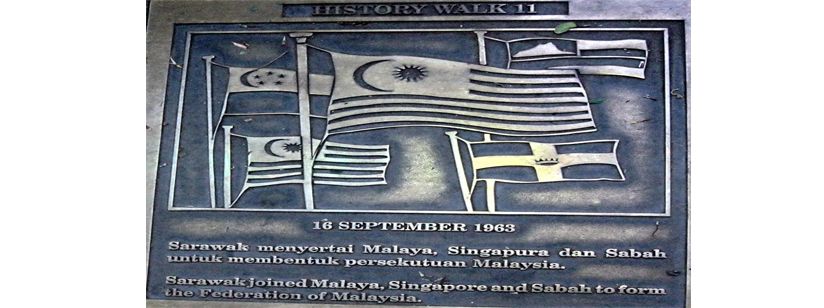

September 16 Tun Abang Openg is sworn in as the fi rst Yang Di- Pertua Negeri Sarawak. Prime Minister of Malaysia Tunku Abdul Rahman reads the Proclamation of Malaysia in front of the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong, Raja- Raja Melayu and thousands of citizens at Stadium Merdeka to mark the birth of a new country named, the Federation of Malaysia.

He says: “The great day we have long awaited has come at last – the birth of Malaysia.

In a warm spirit of joy and hope ten million people of many races in all the states of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah now join hands in freedom and joy.”

Khir Johari reads Proclamation of Malaysia as the representative of the Prime Minister to mark the independence of Sarawak in the presence of Tuan Yang Terutama Tun Abang Openg, Chief Minister Datuk Stephen Kalong Ningkan, the State Cabinet and the people at Padang Sentral (now Padang Merdeka), Kuching, and in all divisions of Sarawak.

(Chronology is translated from the offi cial 45th anniversary souvenir book, ‘Perayaan 45 Tahun Sarawak Maju Dalam Malaysia, 1963 – 2008).